The next time you find another angry message board about unhoused people in Venice, please refer them to these facts.

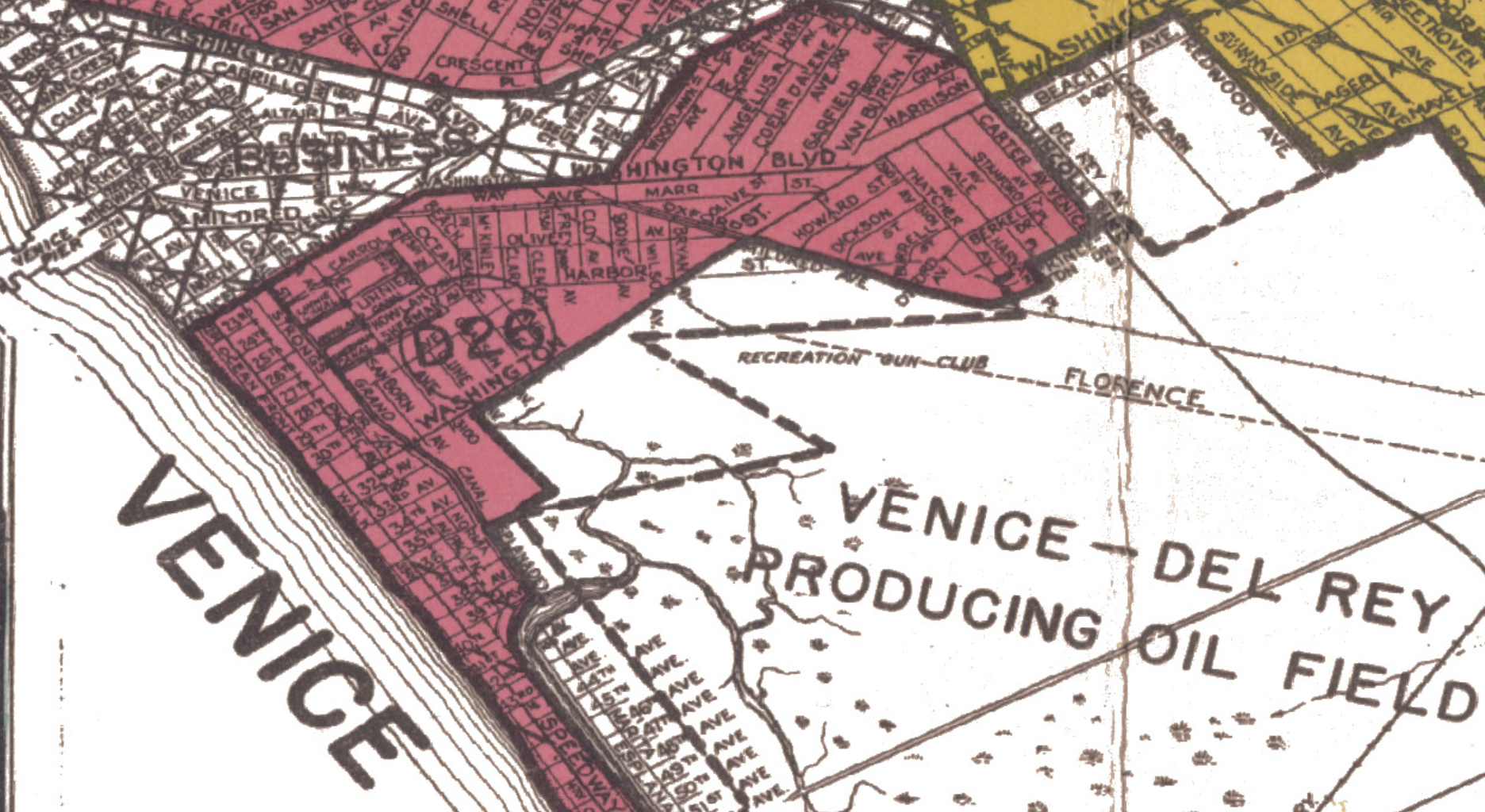

Venice was redlined in the 1930s for 15% of its area containing families of “Mexican, Japanese, and Italian” origins and 4% “Negroes,” according to written records. The decision in the 1940s to funnel federal money for housing away from the area is no small part of why today’s homelessness along its beachsides, followed by policing, have markedly increased over the years.

Appraisers for the federal government arrived to Venice in 1939 and misleadingly claimed, “Many mortgage institutions will not operate in area.” They also went on to call the community “blighted” for its multi-ethnic workers and families. At this point, if you’ve read about redlining on this blog, it should be clear that such language by government officials was not only malicious, but consequential in that disparaging language against non-whites was instrumental for states and cities to decide where wealth and poverty would reside, respectively.

Over time, as the militaristic takeover of Echo Park this past March showed, public officials in L.A. would largely choose to expend public tax dollars to formerly redlined areas in the form of policing, that is, policing poor people in these communities on the basis of “Neighborhood Watch” and also “super-predator” theories, which supposed that youth and working age-adults in such “slum” areas were simply more predisposed to commit crime given their impoverished living conditions. Of course, in order for these theories to work, city officials just had to ignore the fact that opportunities for wealth and home-ownership for Black and immigrant communities in “slums” were choices first taken away from them by the federal government and complicit municipal and state actors.

But don’t let what escaped real estate appraisers in the 1940s escape you in the 2020s: Disinvestment in non-white communities and the inverse for whites was and remains backwards planning since whiteness could not and still cannot survive as an investment without supportive non-white labor pools nearby. The very development of the Venice canals in the early 1900s was only possible because of Black labor. In fact, Black labor was so crucial to the construction of Venice beach that families were moved out to what would become the Oakwood neighborhood in order to speed up work for the grand opening of the famous beachside in 1905.

Yet when federal appraisers arrived in 1939, on seeing “Black, Mexican and Japanese” residents alongside white European immigrant households, they were under strict orders from the Federal Housing Administration’s 1936 manual:

“The Valuator should investigate areas surrounding the location to determine whether or not incompatible racial and social groups are present, to the end that an intelligent prediction may be made regarding the possibility or probability of the location being invaded by such groups. If a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes.”

Ironically enough, this logic, claiming that any and all whites interested in a home near Venice beach would turn away from the area on learning of Black and immigrant communities like Oakwood, was proven false by white influxes into Venice starting in the 1980s. Yet it’s nevertheless the logic of entitled homeowners associations in the neighborhood today, who assert as unscientifically as their peers did when “separate but equal,” or Jim Crow policy, was still law, that the very existence of unhoused people in the area depresses property values and “brings in crime,” something we’ll get back to in a moment.

For now, just note that housing shortages for Black and non-white immigrant communities in Oakwood would only be exacerbated after the population boom spurred by the end of World War II because of the pseudoscience of real estate assessments over the “compatibility” of such communities with the dominant white order.

Racial disinvestment against areas like Oakwood would continue well after the Fair Housing Act of 1968, when redlining was outlawed, with one exception: investment in policing budgets and details to patrol Black and Latino families in the vicinity. Like their contemporaries to the Southeast in Watts, then, despite the Fair Housing Act families were still discriminated in housing as well as in employment and educational opportunities, thus making them more vulnerable to L.A.’s expanding carceral state.

A real estate boom would hit the community in the late 1980s, abetted by an accompanying surge of policing, pushing major swaths of Blacks out of the historic neighborhood in particular. By 1990, the Black population in Oakwood fell by eight percentage points down to 22% of the area, a substantial drop from a high of 44% in 1970. Latinos and whites, by contrast, increased by five and three percentage points, to make up 50% and 26% of the Oakwood population in the years before the Rodney King rebellion, respectively.

By 2000, the Black population in Oakwood fell again by another seven percentage points to 15% of the area, while the Latino population saw its first decline after four decades of growth by three percentage points down to 47%. Over the course of the new millennium, however, Latinos would continue to leave Oakwood, following in the footsteps of Blacks, whose displacement from the area began as early as when Latinos grew to comprise half of households there in 1970. As of 2019, the percentage of Black families in the area was less than 12%, while the Latino population decreased to 30%. White families, by contrast, now form 73% of the Oakwood neighborhood, something that must have seemed unimaginable to many Black and Latino youth policed up and down its corners in the early 1990s.

A gang injunction by the LAPD in Oakwood was initiated in 1999, even as research showed that “gangs” across L.A. by the 2000s were largely inactive compared to the 1970s and 1980s.

Compounding a dearth of housing and employment opportunities, the injunction would harass and jail generations of working-age Black and Latino residents in the area until an ACLU lawsuit slowed it down in 2016. Yet by the early 2010s, as Brown families to the northeast in Echo Park would also find, the damage was done. In the words of one life-long resident of Oakwood from a 2018 interview:

“Families moved out to get their kids away from the gang injunction because you couldn’t be anywhere in Venice and not get stopped or harassed or arrested by the police if they deemed you a gang member.”

Additionally, an inspection of data from the Million Dollar Hoods project shows that over a five year period, from 2012 – 2017, police made over 3,300 arrests in the Venice beach area, with Black and Latinos accounting for 57% of arrests despite making up just 27 percent of the area’s population by 2008. Black men in particular were arrested at a rate seven times higher than their share of the population.

Today, Council District 11, where Venice and Santa Monica are based, stands to see a continued decline of Black and Latino households at the same time that homelessness continues to soar for these two groups across Los Angeles. Since 2011, CD-11’s rate of unhoused people has grown by 160% to more than 3,200 people, making it the sixth most impacted district in Los Angeles today, and by extension, another resourceful hub for police activity.

This is because while the number of unhoused people in L.A. grew by leaps and bounds over the 2010s, research suggests that homelessness, followed by policing apparatuses and their budgets, grew most in formerly redlined areas.

For example, in 2019, just three of fifteen districts in L.A. contained 41% of the city’s homeless population, all three of which were heavily redlined or marked for disinvestment for their Black and immigrant residents during the federal housing administration’s development programs; neighborhoods in these areas include Skid Row and Boyle Heights, South Central or South Los Angeles, and Leimert Park and the Crenshaw corridor, where rapper Nipsey Hussle was slain in March 2019.

We also now return to the question of “crime,” particularly as it’s said to concern unhoused people. In the 1980s and 1990s, white liberal and conservative politics asserted that crime in L.A. was largely due to Black and immigrant “gangs.” Today, homeowners associations and their backers increasingly attribute crime to unhoused people, nearly 3/4ths of whom are Black and Latino in Los Angeles. Yet since the early 1990s through 2019, while homelessness increased in the city, reports of violent and “property crimes” across the nation–and in L.A. County–generally fell by more than half.

As recently as 2019, there were approximately 555 violent crimes per 100,000 people, compared to nearly 1,800 such crimes reported in 1990. There were also 2,200 property crimes per 100,000 people (not including arson) in 2019, though compared to 5,700 such crimes reported in 1990.

The point is so important it merits repetition: While homelessness in Los Angeles County has increased yearly since the early 1990s, both violent and property related crimes here have largely continued to fall since their 1990 levels.

But might the drop in crime be explained by the increased police budgets after all? Contrary to such rhetoric from police unions and their public official liaisons, “more cops” have not equaled more public safety. As Aya Gruber recently noted in a brilliant essay on “bluelining,” or police-patrol as a new form of redlining against historically discriminated communities of color, experts have long held that random preventative patrols, along with rapid response time to calls, neither reduce crime nor induce fear in people considering a criminal act. Additionally, Gruber points out:

“Researchers have also determined that ‘proactive policing,’ which includes ‘quality of life’ offenses, street sweeps, and stop-and-frisks, does not reduce, and in fact, may increase, crime (emphasis J.T.’s).”

If not for the continued policing of non-white bodies via gang injunctions and increasingly due to “homelessness,” then, exactly where would police have gone over the last 30 years? Something tells this writer that “preventing,” or rather responding, to 500 violent crimes and 2,200 property crimes per 100,000 households to the tune of billion$ would be more difficult for police unions and public officials in L.A. to justify annually. Yet it’s increasingly the case as more of us bear down on the city and county’s historic over-expenditures on its police state.

As author Alex Vitale noted in The End of Policing (2017): “The reality is that the police exist primarily as a system for managing and even producing inequality by suppressing social movements and tightly managing the behaviors of poor and nonwhite people: those on the losing end of economic and political arrangements.”

Moreover, in Los Angeles, there is overwhelming evidence to show why policing non-white communities into submission is not a sustainable path for the city, state or federal government. This August will mark 56 years since the war-zone in Watts, when the LAPD and Mayor Yorty called on National Guard troops to descend on Black bodies in the South L.A. community after their rebellion against continued police brutality there. The reign of fire led to the police murder of 26 civilians, the injuries of thousands more, and subsequent “riots” in response to over-policing and disinvestment against Black communities in sister cities over the following years.

This past April marked 29 years since 64 people lost their lives across Los Angeles, including ten murdered by police, while 54 others were killed amid looting and civil unrest; 3/4ths of those killed were Black, Asian-American and Latino. And as with thousands of other deaths and damages in cities all over the U.S. following the 1960s–each loss of life and damage was preventable, pronouncing the indignity of the “red line” against non-white communities well beyond the 1930s.

What’s also true is that a major part of why L.A. & Cali have always operated–dangerously–in isolation is because of Washington D.C’s refusal to rein in their correspondents when acting unilaterally against “poor” people. Yet as the progenitor or “forefather” of the Federal Housing Administration program that has segregated Black and immigrant neighborhoods in the inner city for nearly 100 years now, Washington D.C. is not extricable from discussions of equity, reparations, and reconciliation for housing, employment, and other opportunities taken from us.

In concert with a new civil rights movement, then, picking up where our first civil rights leaders left off, it’s now time for communities, from Oakwood and all of Venice, to Echo Park and beyond, to mark every dollar lost on policing rather than resourcing our neighborhoods. In a fair hearing, whether on the streets of D.C., or before the United Nations, each dollar represents what we are owed—with interest—in a new, New Deal for the 21st century.

J.T.